One of the most vital aspects of a novel that's often forgotten by rookie authors is the "so what?" or, in other words, the consequence. What happens if your main character fails in his quest? What if she doesn't break the curse? What if he joins the dark side? What if they don't reach the Emerald City? What is the consequence? What's at stake?

Part of thinking about your story in terms of consequences is thinking about the actions that precede the consequences. So basically: this action leads to this consequence, which leads to more action. Sometimes, consequences stem from your main character's decisions. Other times, the consequence is created by others' actions, which in turn affect the main character. Whatever the case, in a great story, something is always at stake.

Let's take The Hunger Games, by Suzanne Collins, as an example. Katniss Everdeen has one thing she loves completely: her little sister, Prim. When Effie Trinket draws Prim's name (action), Prim must fight to the death in the games (consequence). But Katniss cannot bear to watch her sister fight and inevitably die, so she volunteers to take Prim's place (action) and engages in a fight to the death (consequence).

What would have happened had the story been more like, "Prim sat at home, and one day she died. And Katniss cried." That's hardly a story. Even, "Prim's name was drawn, she fought in the games, and she died. Katniss cried." That's a little bit better, but still not a bestseller. But this, "Prim's name was called, Katniss cried out that she would take her place, and Katniss was immediately taken away from her family to go fight to the death in the games." Now that's a story people want to read. That's bestseller material.

So what is the one thing that matters most to your main character? Is it family? Honor? Love? Survival? Whatever it is, take it away. But remember that it needs to be a consequence of someone's actions. For Katniss, her family was at stake. And then her own life hung in the balance.

Now, it was her choice to volunteer to take her sister's place in the games; it was her actions that forced her to deal with the consequence. But whose actions forced her to make that decision? The Capitol. And that is how an antagonist is born. The actions the villain takes against the hero are a means of revealing the villain. (If you want to throw your readers off the trail of the antagonist, have him take actions that benefit the hero at first. Then later, reveal that his actions were all just to further his plot to destroy the hero in some way.)

Every character or group will take action in your story. Does Katniss volunteer? Does Peeta throw the bread? Does Haymitch send supplies? These actions will all lead to consequences and future actions. Imagine how things would be different if any of these characters (or your own characters) had made different decisions. The consequences would be different. If you are stuck in writer's block, look at the consequences of your characters' actions. Make the consequences more severe. Put something even more important on the line. Does the character have anything left to lose? If yes, then put that on the line. If no, then put her life on the line.

The most important thing to remember is that without any consequences, there's no story. If Prim's name was drawn to receive a sack of potatoes, then Katniss would pat Prim on the head and they would go home. And that would be it. Or would it? Even the most innocent of actions can have dire consequences if you, the author, make it so. What if the sack of potatoes had been poisoned? What if the rest of the town was starving and they end up breaking into Katniss's house just for the potatoes? What if both of those things happened and the members of the town began dying off because of the poison? And then comes the question: who poisoned the potatoes?

Though a story about poisoned potatoes may be interesting, a story about a girl who has to fight other teenagers to the death may be a bit more interesting. So don't be afraid to raise the stakes. It is only when the consequence is so terrible that the character feels like she has no choice. And it's when she feels like she has no choice that she makes a decision. Does she sit back? Or does she stand up? Is she ready to face the consequences of her decision? Well, ready or not, she will have to.

So, you're an author and you write a book with high stakes and drastic consequences (action). So what? Well, readers will stick around to see what happens (consequence), and maybe you'll be the next bestseller (even better consequence).

Monday, June 24, 2013

Friday, June 14, 2013

ABDs of Plot, Part 2

Read part 1

Apply this excellent example of the ABDs pattern to your own characters as you build the climax of your story. Because of unique backgrounds, each of your characters has separate longing and desires that drive their choices and actions throughout the tale. Thus your story develops, building up clashes of desire as well as conflicts preventing the fulfillment of desire, until finally something or someone is forced to choose, to struggle against a foe, to face the truth—at the risk of losing something very dear, possibly even their own life.

All roads lead to the climax, so the details you include should supply readers enough to chart out maps of strategy and build tension bridges all the way to the point of no return. Think of the climax as the thing(s) that your reader will never get back once your characters summit that paramount crisis.

Take the time to map out what you want each character to have learned or lost, gained or forfeited by the plot's end. The plot is largely completed at the climax because the driving components of the story have crashed head on. The denouement allows for the dust to clear and settle, accounts for damage and casualties, and offers a glimpse into the future of the survivors. Sometimes an epilogue can close the story, sometimes the promise of a sequel will take care of larger loose ends.

Whatever comes after the climax needs to fit the development and mood and tone of the preceding scenes and interaction between characters. But in the end, the story must end. And at some point in your background development, you must know to what end you're writing. If you don't know (and some of us are discovery writers who find the ending the closer we get to it), keep writing—don't surrender the story to a premature ending! Revisit and reapply the ABDs to every chapter until the ending reveals itself to you. Your characters will give up their secrets, the setting will settle at last, the dialogue will have the last word—and you'll have a bestseller.

And there you have it—a great start to laying your story down, letter by letter. Now you know the ABDs, next time won't you write with these!

Climax

The climax is "the most intense, exciting, or important point of something; a culmination or apex." Let's use The Lord of the Rings. There they stand, Frodo and Sam, at the most important point in their journey to destroy the one ring, and Frodo manifests a change of heart. In comes Gollum, a character representing a culmination of years of servitude and devotion to the ring, and a scuffle over the ring ensues.Sam got up. He was dazed, and blood streaming from his head dripped in his eyes. He groped forward, and then he saw a strange and terrible thing. Gollum on the edge of the abyss was fighting like a mad thing with an unseen foe. To and fro he swayed, now so near the brink that almost he tumbled in, now dragging back, falling to the ground, rising, and falling again. And all the while he hissed but spoke no words.

The fires below awoke in anger, the red light blazed, and all the cavern was filled with a great glare and heat. Suddenly Sam saw Gollum’s long hands draw upwards to his mouth; his white fangs gleamed, and then snapped as they bit. Frodo gave a cry, and there he was, fallen upon his knees at the chasm’s edge. But Gollum, dancing like a mad thing, held aloft the ring, a finger still thrust within its circle. It shone now as if verily it was wrought of living fire.

"Precious, precious, precious!" Gollum cried. "My Precious! O my Precious!" And with that, even as his eyes were lifted up to gloat on his prize, he stepped too far, toppled, wavered for a moment on the brink, and then with a shriek he fell. Out of the depths came his last wail Precious, and he was gone.

–The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, J. R. R. TolkienDid you notice the ABDs in play? The scene is clearly set and the action is quick and fluid; the story's background elements are merging in a pinnacle moment of development: the principal characters are finally brought into the critical situation; and the climatic struggle between betrayal and loyalty risks to thwart the characters' ultimate goal!

Apply this excellent example of the ABDs pattern to your own characters as you build the climax of your story. Because of unique backgrounds, each of your characters has separate longing and desires that drive their choices and actions throughout the tale. Thus your story develops, building up clashes of desire as well as conflicts preventing the fulfillment of desire, until finally something or someone is forced to choose, to struggle against a foe, to face the truth—at the risk of losing something very dear, possibly even their own life.

All roads lead to the climax, so the details you include should supply readers enough to chart out maps of strategy and build tension bridges all the way to the point of no return. Think of the climax as the thing(s) that your reader will never get back once your characters summit that paramount crisis.

Ending

Well, as they say, what goes up must come down. After the climax, comes the denouement. After the fable, Aesop states the moral. The end wraps up the overarching element that brought all the characters together. We may plot Lord of the Rings as a story about a ring that needs to be destroyed, but the concluding lines after the climactic scene reveal a deeper plot: a story about loyalty and enduring friendship."Your poor hand!" he said. "And I have nothing to bind it with, or comfort it. I would have spared him a whole hand of mine rather. But he’s gone now beyond recall, gone for ever."

"Yes," said Frodo. "But do you remember Gandalf’s words: Even Gollum may have something yet to do? But for him, Sam, I could not have destroyed the Ring. The Quest would have been in vain, even at the bitter end. So let us forgive him! For the Quest is achieved, and now all is over. I am glad you are here with me. Here at the end of all things, Sam."

–The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, J. R. R. TolkienOne purpose of a story's ending is to extract a moral or offer a broader conclusion. It may summarize or philosophize, leave the reader stunned or in happy tears, but what it must not do is stop the plot before it's finished. Throughout the entire story, the elements intersect and merge to propel us through the twists and turns and over the obstacles and around the bends. If those elements all intertwined are not somehow collectively or individually tied off, your credibility and likability as an author will promptly unravel.

Take the time to map out what you want each character to have learned or lost, gained or forfeited by the plot's end. The plot is largely completed at the climax because the driving components of the story have crashed head on. The denouement allows for the dust to clear and settle, accounts for damage and casualties, and offers a glimpse into the future of the survivors. Sometimes an epilogue can close the story, sometimes the promise of a sequel will take care of larger loose ends.

And there you have it—a great start to laying your story down, letter by letter. Now you know the ABDs, next time won't you write with these!

Labels:

action,

background,

climax,

development,

ending,

plot,

story,

tips,

writing

Monday, June 10, 2013

The ABDs of Plot

Yes, usually it's the ABCs of something, but if you tend toward the slightly dyslexic (like I sometimes do) you won't find the following list out of sorts. While mnemonically muddled, it still includes the first five letters of the alphabet, so it's easy enough to remember.

Action

Background

Development

Climax

Ending

Boom, your story's movin'.

Writers will often have a general idea of where their novels will start and end, but it's the road from beginning to end that provides the composition "adventure." The middle ground is riddled with alignment-destroying plot-holes and block after block of blocks, which is, ironically, the precise kind of rocky adventure we wish would permeate our paragraphs when our stories are making no progress.

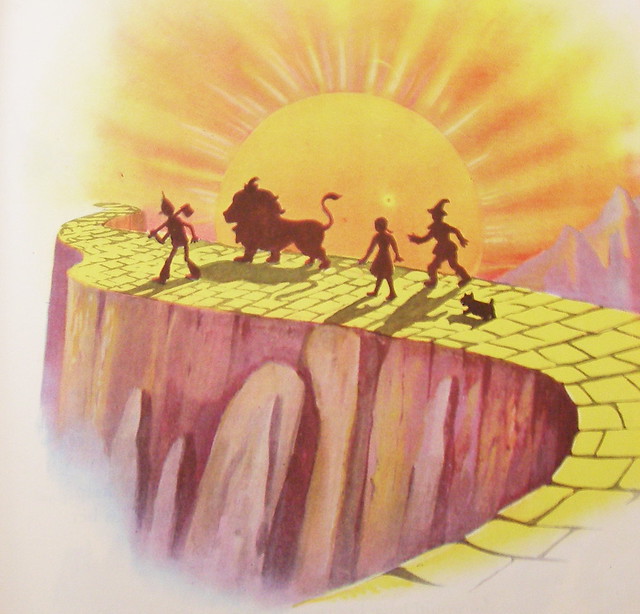

When you're struggling to get from one end of your story to the other, remember the ABD building blocks. Stories are a matrix made up of many layers of beginnings and ends: scenes (which are ideally shaped out of action), background, and development. Chapter after chapter you'll find yourself repeating the same arcs as you build each scene in your story because that's what stories do. The road is paved one yellow brick at a time.

This post will be published in two segments: first the action, background, and development, then the climax and ending. Both are aimed toward helping you get the middles of your story paved so smoothly that readers will be baffled you ever battled writer's block at all.

Labels:

action,

background,

climax,

development,

ending,

plot,

story,

tips,

writing

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)